Discurso sobre la dictadura ante el Parlamento Español

Juan Donoso Cortés

4 de enero de 1849

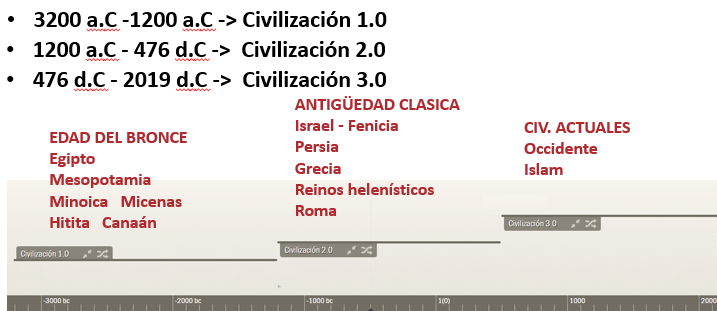

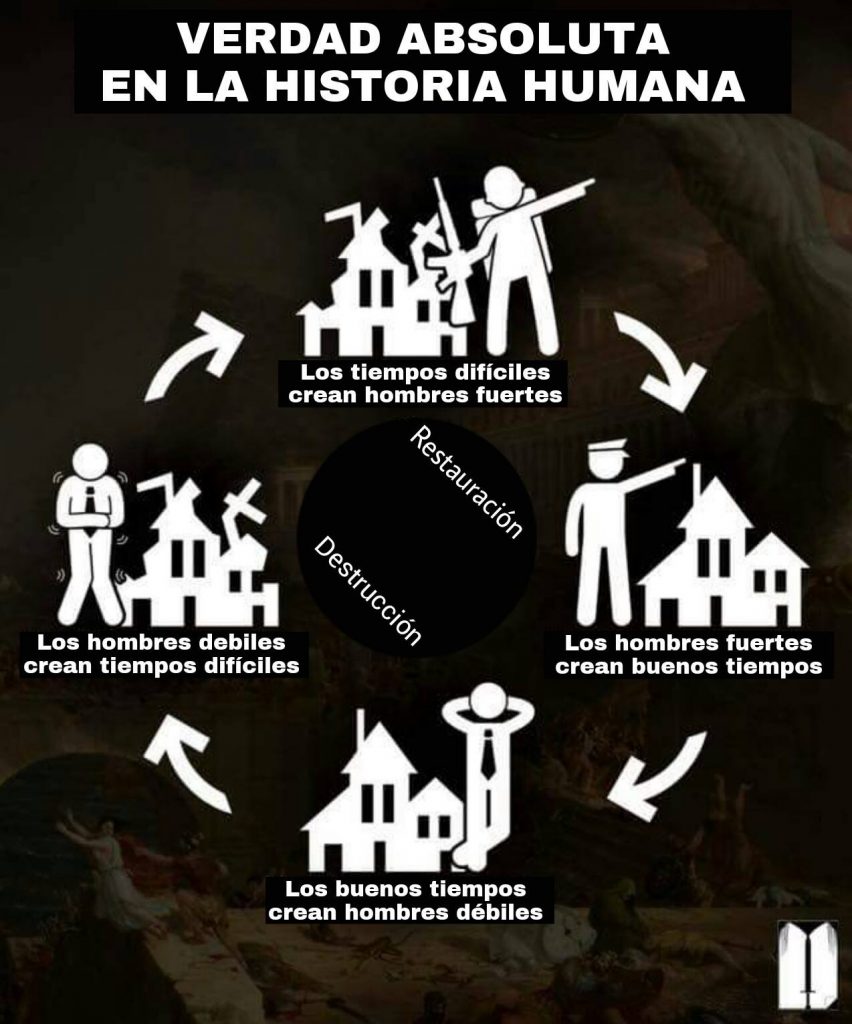

Señores, no hay más que dos represiones posibles, una interior y otra exterior; la religiosa y la política. Estas son de tal naturaleza, que cuando el termómetro religioso esta subido, el termómetro de la represión política está bajo; y cuando el termómetro religioso está bajo, el termómetro político, la represión política, la tiranía esta alta. Esta es una ley de la humanidad, una ley de la historia.

Y si no, señores, ved lo que era el mundo, ved lo que era la sociedad que cae al otro lado de la Cruz, decid lo que era cuando no había represión interior, cuando no había represión religiosa. Entonces aquella era una sociedad de tiranías y de esclavos. Citadme un solo pueblo donde no haya esclavos y donde no haya tiranía. Este es un hecho incontrovertible, este es un hecho incontrovertido, este es un hecho evidente.

La libertad, la libertad verdadera, la libertad de todos y para todos no vino al mundo sino con el Salvador del mundo. Este también es un hecho incontrovertido, es un hecho confesado hasta por los mismos socialistas que lo confiesan. Los socialistas llaman a Jesús un hombre divino, y los socialistas hacen más, se llaman sus continuadores. ¡Sus continuadores, Santo Dios! ¿Ellos, los hombres de sangre y de venganzas, continuadores del que no vivió sino para hacer bien; del que no abrió la boca sino para bendecir; del que no hizo prodigios sino para librar a los pecadores del pecado, a los muertos de la muerte; el que en el espacio de tres años hizo la revolución más grande que han presenciado los siglos, y la llevó a cabo sin haber derramado más sangre que la suya?

Señores, os ruego me prestéis atención; voy a poneros en presencia del paralelismo más maravilloso que ofrece la historia. Vosotros habéis visto que en el mundo antiguo, cuando la represión religiosa no podía bajar más porque no existía ninguna, la represión política subió hasta no poder más, porque subió hasta la tiranía. Pues bien, con Jesucristo, donde nace la represión religiosa, desaparece completamente la represión política. Es esto tan cierto, que habiendo fundado Jesucristo una sociedad con sus discípulos, fue aquella la única sociedad que ha existido sin gobierno. Entre Jesús y sus discípulos no había más gobierno que el amor del Maestro a los discípulos y el amor de los discípulos al Maestro. Es decir, que cuando la represión [religiosa interior] era completa, la libertad [política] era absoluta.

Sigamos el paralelismo. Llegan los tiempos apostólicos, que los estenderé, porque así conviene ahora a mi propósito, desde los tiempos apostólicos propiamente dichos, hasta la subida del cristianismo al Capitolio en tiempo de Constantino el Grande.

En este tiempo, señores, la religión cristiana, es decir la represión religiosa interior, estaba en todo su apogeo; pero aunque estaba en todo su apogeo, sucedió lo que sucede en todas las sociedades compuestas de hombres, que comenzó a desarrollarse un germen, nada más que un germen de licencia y de libertad religiosa. Pues bien, señores, observad el paralelismo: a este principio de descenso en el termómetro religioso corresponde un principio de subida en el termómetro político. No hay todavía gobierno, no es necesario el gobierno, pero es necesario ya un germen de gobierno. Así en la sociedad cristiana entonces no había de hecho verdaderos magistrados, sino jueces árbitros y amigables componedores, que son el embrión del gobierno. Realmente no había más que eso; los cristianos de los tiempos apostólicos no tuvieron pleitos, no iban a los tribunales, decidían sus contiendas por medio de árbitros. Obsérvese, señores, cómo con la corrupción va creciendo el gobierno.

Llegan los tiempos feudales, y en estos la religión se encuentra todavía en su apogeo, pero hasta cierto punto viciada por las pasiones humanas. ¿Qué es lo que sucede, señores, en este tiempo en el mundo político? Que ya es necesario un gobierno real y efectivo, pero que basta el más débil de todos, y así se establece la monarquía feudal, la más débil de las monarquías.

Seguid observando el paralelismo. Llega, señores, el siglo XVI. En este siglo, con la gran reforma luterana, con ese grande escándalo político y social, tanto como religioso, con ese acto de emancipación intelectual y moral de los pueblos, coinciden las siguientes instituciones. En primer lugar, en el instante, las monarquías, de feudales, se hacen absolutas. Vosotros creeréis, señores, que más que absoluta no puede ser una monarquía: un gobierno, ¿qué puede ser más que absoluto? Pero era necesario, señores, que el termómetro de la represión política subiera más, porque el termómetro religioso seguía bajando; y con efecto subió más. ¿Y qué nueva institución se creó? La de los ejércitos permanentes. ¿Y sabéis, señores, lo que son ejércitos permanentes? Para saberlo, basta saber lo que es un soldado: un soldado es un esclavo con uniforme. Así, pues, veis que en el momento en que la represión religiosa baja, la represión política sube al absolutismo, y pasa más allá. No bastaba a los gobiernos ser absolutos; pidieron y obtuvieron el privilegio de ser absolutos y tener un millón de brazos.

A pesar de esto, señores, era necesario que el termómetro político subiera más, porque el termómetro religioso seguía bajando; y subió más. ¿Qué nueva institución, señores, se creó entonces? Los gobiernos dijeron: tenemos un millón de brazos y no nos bastan; necesitamos más, necesitamos un millón de ojos; y tuvieron la policía, y con la policía un millón de ojos. A pesar de esto, señores, todavía el termómetro político y la represión política debían subir, porque a pesar de todo, el termómetro religioso seguía bajando; y subieron.

A los gobiernos, señores, no les bastó tener un millón de brazos; no les bastó tener un millón de ojos; quisieron tener un millón de oídos, y los tuvieron con la centralización administrativa, por la cual vienen a parar al gobierno todas las reclamaciones y todas las quejas.

Y bien, señores; no bastaba esto, porque el termómetro religioso siguió bajando, y era necesario que el termómetro político subiera más. ¡Señores, hasta dónde! Pues subió más.

Los gobiernos dijeron: no me bastan para reprimir, un millón de brazos; no me bastan para reprimir, un millón de ojos; no me bastan para reprimir, un millón de oídos; necesitamos más: necesitamos tener el privilegio de hallarnos a un mismo tiempo en todas partes. Y lo tuvieron; y se inventó el telégrafo [Nota: en nuestra época, se inventó Internet y el smartphone, que nos vigilan a todos].

Señores, tal era el estado de la Europa y del mundo cuando el primer estallido de la última revolución vino a anunciarnos, a anunciarnos a todos, que no había bastante despotismo en el mundo; porque el termómetro religioso estaba por bajo de cero. Ahora bien, señores, una de dos…

Yo he prometido, y cumpliré mi palabra, hablar hoy con toda franqueza.

Pues bien, una de dos : o la reacción religiosa viene o no : si hay reacción religiosa, ya veréis, señores, como subiendo el termómetro religioso comienza a bajar natural, espontáneamente, sin esfuerzo ninguno de los pueblos, ni de los gobiernos, ni de los hombres, el termómetro político, hasta señalar el día templado de la libertad de los pueblos : pero si por el contrario, señores, y esto es grave [..]; pues bien, señores, yo digo que si el termómetro religioso continúa bajando, no sé adónde hemos de parar. Yo, señores, no lo sé, y tiemblo cuando lo pienso. Contemplad las analogías que he puesto a vuestros ojos; y si cuando la represión religiosa estaba en su apogeo no era necesario ni gobierno ninguno siquiera, cuando la represión religiosa no exista, no habrá bastante con ningún género de gobierno, todos los despotismos serán pocos.

Señores, esto es poner el dedo en la llaga, esta es la cuestión de España, la cuestión de Europa, la cuestión de la humanidad, la cuestión del mundo.

Considerad una cosa, señores. En el mundo antiguo la tiranía fue feroz y asoladora, y sin embargo esa tiranía estaba limitada físicamente, porque todos los Estados eran pequeños, y porque las relaciones internacionales eran imposibles de todo punto; por consiguiente en la antigüedad no pudo haber tiranías en grande escala, sino una sola, la de Roma. Pero ahora, señores, ¡cuán mudadas están las cosas!

Señores, las vías están preparadas para un tirano gigantesco, colosal, universal, inmenso; todo está preparado para ello: señores, miradlo bien; ya no hay resistencias ni físicas ni morales: no hay resistencias físicas, porque con los barcos de vapor y los caminos de hierro no hay fronteras; no hay resistencias físicas, porque con el telégrafo eléctrico no hay distancias; y no hay resistencias morales, porque todos los ánimos están divididos y todos los patriotismos están muertos. Decidme, pues, si tengo o no razón cuando me preocupo por el porvenir próximo del mundo: decidme si al tratar de esta cuestión no trato de la cuestión verdadera.

Una sola cosa puede evitar la catástrofe, una y nada más: eso no se evita con dar más libertad, más garantías, nuevas constituciones; eso se evita procurando todos, hasta donde nuestras fuerzas alcancen, provocar una reacción saludable, religiosa. Ahora bien, señores: ¿es posible esta reacción? Posible lo es: pero ¿es probable? Señores, aquí hablo con la más profunda tristeza: no la creo probable. Yo he visto, señores, y conocido a muchos individuos que salieron de la fe y han vuelto a ella: por desgracia, señores, no he visto jamás a ningún pueblo que haya vuelto a la fe después de haberla perdido.

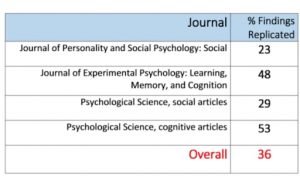

Les ciències socials son les pitjors pero es comú en tota la ciència

Les ciències socials son les pitjors pero es comú en tota la ciència